One of the problems with chiropractic is people don’t like going to the chiropractor for the same reasons as the doctor. It can be a hassle to schedule, out of the way, frustrating to deal with insurance, and often expensive after dealing with insurance. But lump in a stark lack of awareness (50% of Americans don’t know what ‘chiropractic’ means) and a healthy dose of fear (30% know what it means but are scared to try), and it’s easy to understand why just 16% of adults visit a chiropractor each year (2017) while over 60% visit a dentist and over 80% visit a physician.

It could be natural that chiropractic reaches a smaller portion of the population as it is a form of alternative care. But it seems odd that the practice is severely underutilized in a core area — back pain — especially in light of patient reviews.

(Call it bias or insight, I happen to have had a great experience with one myself.)

39% of U.S. adults suffered from back pain within the previous three months (2019). Further, an estimated 80% of U.S. adults suffer from back pain at some point in their life. Of those who did visit a chiropractor, 77% considered the treatment “very effective.” Chiropractic is clearly more relevant than its current representation would indicate, and patients view the treatment favorably.

But to answer, “why is it underutilized?”, we turn to the history.

Chiropractic’s roots trace back to 1895, more than three decades prior to the first health insurance plan. At this point, healthcare was in the early stages of a multi-decade transition to a more formalized system. With this process of formalization came a stricter consideration of treatment methods. As an informal practice with little hard proof surrounding its efficacy, chiropractic was pushed to the outskirts. In fact, several participants who marketed the practice as medical treatment — including D.D. Palmer, “the father of chiropractic” — were jailed for practicing medicine without a license. This proved to be the start of a bitter rivalry between the chiropractic profession and the American Medical Association (AMA), whose influence dominates the medical marketplace.

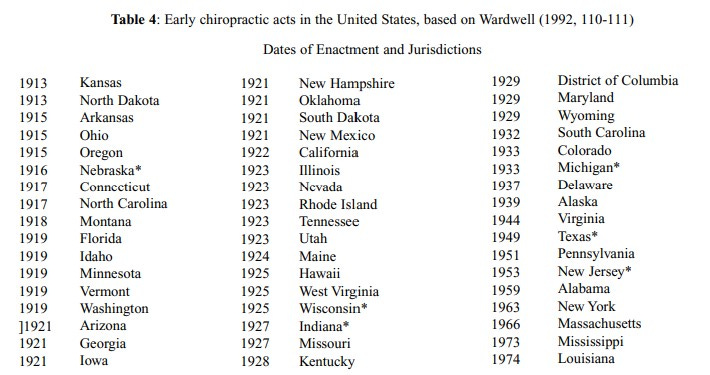

Formal recognition of chiropractic progressed slowly but surely through the first half of the 20th century. By the end of 1963, forty-seven states and the District of Columbia had enacted statutes allowing for the licensure of chiropractors.

But in 1963, the AMA’s combative attitude towards the profession intensified with the creation of the Committee on Quackery (great name), whose explicit purpose was “first the containment of chiropractic and, ultimately, the elimination of chiropractic.” At one point, Joseph Sabatier, Chairman of the Committee, was quoted saying, “rabid dogs and chiropractors fit into about the same category … Chiropractors were nice but they killed people.”

Regardless of whether the Committee was created with good intentions (valid concerns) or bad (to preserve the profits of medical doctors), it undoubtedly made a lasting impact on the perception of chiropractic. Although disbanded in 1974 (after chiropractic achieved licensing in all fifty states, and chiropractic services had become reimbursable through Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance), the Committee definitely did some damage to perception.

In 1975, shortly after the Committee’s disbandment, a conference sponsored by the National Institutes of Health spurred the first real research on chiropractic. Research trials started slowly, picked up steam in the late 1980s, and by the 1990s, the government bestowed the first federal grants for chiropractic study.

Also in 1975, four chiropractors filed an antitrust suit against the AMA for its actions to prevent the expansion of chiropractic treatment. Twelve years later, the judge ruled in Wilk v. AMA that the organization acted as a conspiracy to systematically “destroy a licensed profession.” (No monetary damages were sought, just acknowledgement of chiropractic’s legitimacy.)

Decades of mistrust and propaganda means chiropractic has only recently stepped into the mainstream. In 2015, the Joint Commission (accreditation organization for over 20,000 health care systems in the U.S. and every major hospital) added chiropractic to its pain management standard. And in 2017, the American College of Physicians updated its low back pain treatment guideline to recommend non-drug treatment (chiropractic) as the first order of action.

Along its journey from “unscientific cult” to standard form of care, chiropractic has undergone major reputation rehabilitation. In the context of its time to reach a standard of care, it could be the early innings of broader adoption. Only ~8% of U.S. adults visited a chiropractor in 2012; it grew to ~16% in 2018 (the most recent survey), but it’s still well below the 39% who suffer from back pain.

After proving clinical merit, chiropractic could pose a compelling growth story. The challenge is scaling treatment with a relatively small labor pool (many of whom are self-employed in private practice), maintaining a high quality of care, attracting patients (who are generally unfamiliar with the practice), and doing so in an economically sensible manner.

Nice write up - but can you expand on the clinical efficacy of Chiro? What does the evidence say?