My investment philosophy borrows from David Gardner’s optimism for emerging industries, Nick Sleep’s focus on competitive advantage, Warren Buffett’s portfolio concentration, and Peter Lynch’s “invest in what you know”.

Conventional ‘value’ philosophy bets against change. It seeks out companies that benefit from an indefinite continuation of the present circumstance.

Our approach is very much profiting from a lack of change rather than from change.

- Warren Buffett

Unconventional ‘value’ philosophy bets for change. It seeks out companies that either create the future or benefit from the future becoming the present.

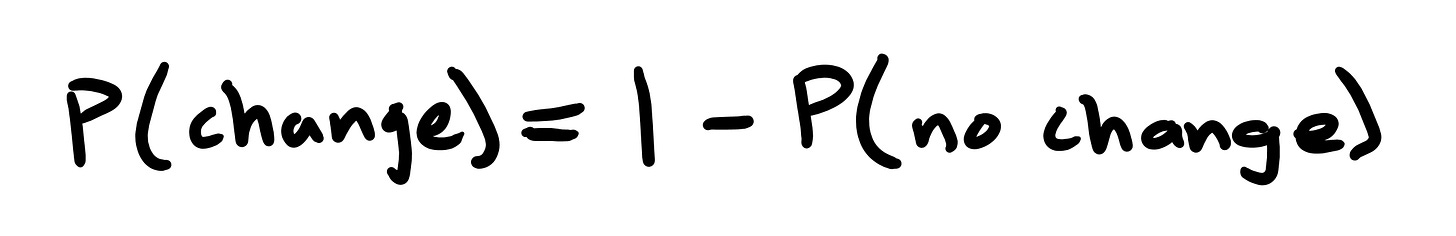

From first principles, a bet for or against change is the same exercise in probability:

This is an oversimplification, of course, but the idea is important. There are two sides to the value coin, which brings up tradeoffs. Betting against change is a more defensive strategy while betting for change is an offensive strategy.

I favor the side of change because I’m aggressively optimistic, and how much you win matters more than how often you win. Radical change creates the potential for radical upside. There’s no free lunch, of course—you pay with uncertainty—but I’m willing to shoulder some heightened risk while I have few financial obligations and a lifetime of future earnings to cushion any errors in judgment.

You may notice I put quotes around ‘value’ philosophy. I share Warren Buffett’s distaste for the term. It’s redundant! All investing is a ‘value’ judgment on the future. Only hindsight reveals the true definition of ‘value’.

You may also notice I didn’t mention the ‘long term’ horizon. It’s also redundant! By definition, investing is a long term activity; trading is its short term counterpart. If our goal is to compound money, taking the long view is a necessity; it maximizes the exponent in the compounding equation.

The following criteria and questions guide my assessment of a business.

A compounding competitive advantage

A business gets better or worse every day. The direction of the moat is my primary concern: is the moat under construction or under maintenance? I prefer the former: companies with ample room for reinvestment.

If this level of reinvestment defers profits, the situation can become more interesting. I’ve found the market to be excellent at pricing profits; not so much at pricing a competitive advantage that has yet to produce profits.

Business strategy is an essential component of this analysis. How does management plan to build the brand, differentiate the product, create network effects, achieve scale economics, or otherwise cement its leadership position over time?

An important emerging industry

What problem does the company address? What process does it improve? Are existing customers increasing spend? What is the potential customer universe? How profitable are the industries served? How would customers be impacted if the product disappeared? Is the market opportunity regional, national, or global?

Gauging the importance of an emerging industry is far from an exact science, but the activity and characteristics of early customers can hint at the value of the opportunity.

People who prioritize execution in pursuit of a simple vision

A mission statement can be a marketing ploy, but it can also evidence ambition. How large does management envision their impact? Is it realistic?

New markets are created by leaders who are unusually passionate about a simple idea whose value most people fail to grasp. But change isn’t driven by passion; it’s driven by monotonous daily execution. Management’s priority should be taking small steps in the same direction every day. If not, I’m skeptical of the probability of success.

Execution drowns words. What has management achieved in the past? How does it compare to their words? Have they previously executed a difficult ambition? Do they clearly articulate near-term priorities while emphasizing the long-term context?

The level of confidence in the people behind the business is one of the most important considerations when betting on change.

Optionality and speed of innovation

Category creators experiment with a sense of urgency: they are proactive, not reactive. A rapid pace of innovation often foreshadows lasting change.

How quickly do products improve? How often does the company release new products? Does it rely on in-house innovation, or does it benefit from a platform ecosystem? Does it benefit from secular improvements to a core technology?

The direction of innovation is just as important as the pace. Where can the business extend its reach? What solutions can be integrated into a packaged offering?

Optionality is a difficult component of the ‘value’ equation. Therein lies the opportunity.

Proven business model

How does a company make money? Does it get paid upfront? Does it require ongoing investment in inventory? Does the business naturally make more money as it grows?

What are the unit economics? What are profit margins? Why are margins that way? What is an expectation of steady-state capital intensity? How cyclical is the industry?

Financial statements are relatively useless when considered in isolation. An early-stage category creator can be identified only by considering the economic characteristics in the context of strategy. A fundamental reality misunderstood by the market is more indicative of value than a high growth rate or any other numerate factor.

Clean balance sheet

The search for category creators requires entry into the arena of cash-burning / unprofitable entities. I supplement this risk by running a concentrated portfolio.

Stock price volatility is a feature—not a bug—of this approach (provided you have the emotional constitution), but it’s a different equation when the company’s future is in genuine question. For a cash burning entity, I typically require a large net cash balance (able to fund 2+ years of operations) and a clear path to self-sustenance. Strangers are only kind for so long.

Though I eschew the conventional concept of ‘value’ employed at Berkshire, the ‘business owner’ principles are the foundation of my philosophy and pose a series of essential questions.

Would I be comfortable owning the business if the stock market were to close for five years? Do I share management’s vision of the future? Do I understand the plan of execution? Do I agree with the assessment of the market opportunity? Do I see a clear path to a larger, more profitable business over time? Is management properly incentivized to act in the interest of owners over a multi-year period?

Yes is the only acceptable response to these questions.

In closing, I’ll echo the words of Jeff Bezos in his inaugural shareholder letter:

We aren't so bold as to claim that the above is the "right" investment philosophy, but it's ours, and we would be remiss if we weren't clear in the approach we have taken and will continue to take.

Valuation is too nuanced an issue to explore in this essay. I may explore my thoughts in a future dedicated post.

I like how you cover some counter intuitive companies, including those "left for dead" like the broken spac company.