Planet Labs has an enterprise value of just over $300 million, net of a $320 million cash position. The stock is at $2 and change, down almost 80% from its December 2021 SPAC price. Revenue growth has slowed. The company is burning cash. Investors are uncomfortable. And I’ve lost a good chunk of money (on paper).

Fortunately, it doesn’t matter what the stock price says. What’s important is that Planet is a better business in every way today compared to a few years ago. It is still the only company producing a daily scan of the Earth. Its product is vastly improved. The customer base is much larger. Gross profit is multiples of what it was. And the company successfully raised hundreds of millions of dollars to support large investments in its future.

If you own Planet to make a quick buck, this isn’t the article for you. If you own Planet to make money over a long period of time, I encourage you to disregard the headlines. Ignore the widespread criticism of management. Most people are not interested in the business. They’re focused on the stock.

Sticky cash flows & self-reinforcing growth

What’s often misunderstood about Planet is the asymmetry of the long-term investment opportunity. This a story of category creation, and the category is likely to turn into a surprisingly large one.

Kevin Weil (2023 investor day): “Before Planet, there was no such thing as a daily scan of the Earth. It didn't exist. It's a new capability for humanity.”

Brad Smith (President of Microsoft, speaking at Planet Explore 2023): “I’m here for a simple reason. I really feel that what you are doing, and what Planet is doing, is of profound importance to the future of the world.”

Planet sells a now-critical dataset to a thousand customers around the world. There is a larger universe of companies, who look a lot like existing customers, that Planet has yet to reach. Most of these customers have large budgets for exactly what Planet offers. Its data has proved an economic benefit to various industries, and customers have responded by steadily increasing their spend.

These same customers inform Planet’s roadmap. They share which kind of data they would like more of and contribute ideas about how they could extract more value from it. This is a customer-led, self-reinforcing growth formula.

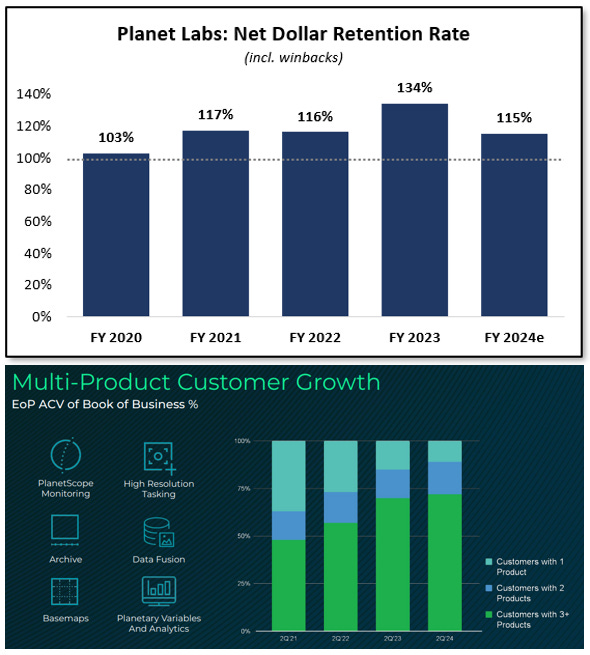

Planet’s job is to execute on that customer input and contribute some ideas of its own. Thus far, it’s proven more than capable. Net dollar retention rate consistently exceeds 100%, and the average number of products per customer is growing steadily. Planet is becoming integrated deeper into their workflows.

The unusual stickiness of data businesses is the heart of the investment case. Data exists a layer below software, so it’s harder to implement (or sell), but it’s harder to rip out. Once it’s in, it generally stays in.

Whereas the value of software tends to decline over time, the value of data tends to increase. As a result, software economics tend to degrade while the economics of data tend to improve over time. This is an important distinction.

Planet doesn’t report explosive top-line growth because it sells data methodically. It has to understand how customers get value from it and work with them to improve. From there, you can build products, create a repeatable sales motion, and accelerate growth. (Accelerating growth is the fourth fundamental truth in “The Economics of a Data Business.” I recommend reading the whole piece.)

Planet is in the early stages of acceleration. The company is just three years into its rebirth as a “product” company, catalyzed by the SuperDove upgrade. An order of magnitude more performant than the original Dove (at the same cost), the new satellites are built specifically for machine learning purposes. In short, the data they produce is a lot more valuable.

SuperDove (not to mention Pelican and Tanager) demonstrates the power of a feedback loop that extends to space system design. Vertical integration allows Planet to move quickly when addressing customer feedback. And all things equal, a greater pace of change (or speed of development) generally increases the probability of success over time.

Planetary Variables are the latest development on the product front. These are horizontal building blocks of data on which businesses can be built. As an example, SwissRe and AXA are building an end-to-end drought insurance business on top of this data.

Elsewhere, large agriculture firms like Bayer, Corteva, Syngenta, etc. are using Planet’s data across nearly every part of their business. Civil governments are building regulation on top of Planet’s data. Utilities are monitoring hundreds of thousands of miles of the grid with Planet’s data. And global NGOs are tracking global deforestation with Planet’s data.

These all provide a foundation for sustained growth over time. Programs like these are not built all at once; they scale over time. And Planet is a key piece of the infrastructure that enables it all. That’s an excellent position to be in.

Increasing returns on capital

A lot of investors overemphasize revenue growth. It’s important, to be sure, but I’d say gross profit growth is more important, and the capital required to deliver that growth is the most important consideration.

Planet has grown gross profit at a 64% CAGR over the last three years. Not many companies can report that kind of number with revenue growing at only 24% annually. It demonstrates unusual operating leverage.

Revenue has more than doubled since 2020, while cost of revenue has remained roughly flat. Planet collects the data only once — it’s a fixed cost — but can sell it to anyone at zero marginal cost. Gross margins expand rapidly as a result.

I estimate PlanetScope is already a 75% gross margin business at only ~$150 million in revenue (using conservative assumptions). Over time, the entire business should reflect a similar gross margin profile.

(Available data is in blue. My assumptions are in red. $218 million is low end of revenue guidance. 52% is low end of gross margin guidance. Each constellation’s cost of revenue is assumed to grow in line with the total.)

This latent profitability is one reason why the company is investing so heavily below the line. Management understands the margin expansion opportunity built into the gross profit line.

My point is simple: the company could likely be profitable today if absolutely necessary. The unit economics are sound, the constellations are automated, and there is minimal cost or risk involved in scaling the core business operations.

Instead of taking these profits, Planet is investing in the future. Doubling the sales team. Acquiring skilled software developers (via VanderSat, Salo Sciences, and Sinergise acquisitions). A lot of this investment is in talent, and that strategy tends to pay off. The leadership of acquired companies are sliding into senior product roles to do exactly what they were doing before, with better inputs and more resources.

Planet is also investing in future data acquisition infrastructure (new space systems like Pelican and Tanager). This is core to Planet’s edge — an ability to design and build constellations quickly. More data yields greater customer value, which supports the aforementioned feedback loop.

Kevin Weil (2022 investor day): “I think we are better at agile aerospace and manufacturing large constellations of satellites quickly and cheaply than anybody else.”

All in all, these are good investments, and sometimes the company isn’t fronting the whole cost. Other people want access to the data enough that they’re willing to bear a portion of the upfront cost; Planet received over $40 million to fund the development of Tanager, for instance.

These partners will have free access to a subset of the data, but this doesn’t really impact Planet; it still owns the satellites, and it costs them nothing to give away data. Whatever they do sell, they make damn near 100% incremental margins from. And the structure is even more advantageous for Planet because the combination of new data with its existing data makes both more valuable.

I would go so far as to say it might be imprudent to not be investing at such a pace, in light of the significant amount of cash lying around and the large greenfield opportunity ahead. And we can be reasonably sure these investments will produce attractive returns over time.

We can’t yet gauge operating-level returns on capital given the ongoing level of investment. But we can try to assemble some numbers. Management has shared that SuperDoves are built with a useful life of 3 years and pay for themselves in the first 3-6 months. Pelican and Tanager are built to <1 year payback periods, with a useful life of 5 years. For the sake of argument, we can see what returns on capital look like using gross profit as the numerator.

The graph tells a compelling story of increasing returns. The 2024 decline reflects the investment in Pelican, which will start to bear fruit this year and should begin to produce positive momentum next year. At such small scale, these returns indicate a rare capital efficiency. Given time, they should translate into attractive metrics at an operating level.

The marketplace

A lot of people think Maxar and BlackSky are Planet’s main competitors. They are, for a certain segment of the market (mainly defense & intelligence). But most customers pay Planet for the daily scan, and that’s the more interesting market opportunity long-term. It’s Planet’s category to create, and it’s unhindered by capacity constraints (unlike high-resolution tasking).

Even for D&I, Planet brings a unique offering to the table: worldwide search. Agencies can go back in time to search for specific things — military evolutions, nuclear silos, activities at a hub, you name it. Synthetaic (Planet’s partner) has created an incredible tool called RAIC that enables this capability. I recommend checking out Kevin Weil’s demo of the program at last year’s investor day.

Back to my point: PlanetScope’s competition is not Maxar or BlackSky. Its competition is free data from public missions. Customers are more often combining Planet’s data with free data than with other paid satellite data. We see evidence of this in European regulatory programs. We see it in many agriculture customers. We see it in many civil agencies. And we see it in the insurance companies.

Free satellite data programs have produced great returns for the public despite exorbitant costs. In 2017, the Landsat program produced an estimated $3.5 billion in economic benefits, up from $2.2 billion in 2011 (8% CAGR). Despite an $800 million upfront cost (enough to operate PlanetScope for over 35 years), this is an attractive return.

Planet’s fundamental innovation is in developing satellites at a low enough cost that customers can justify spending money on the data, rather than settling for free data. Naturally, the company expects to keep some of the value it creates. Given Planet’s data is orders of magnitude better than Landsat, it will be interesting to see the economic benefit it ultimately produces.

This is all a positive market development. It enables the creation of a new business model with profitable unit economics. And at the end of the day, business is the engine of progress. I regret to inform the socialists that profits spur positive change because sustainable profit growth depends on an ability to provide customers with more value over time. Jeff Bezos knew this better than anyone.

Planet recognizes this fact, which is partly why it’s structured as a Public Benefit Corporation. It can scale its business while doing good for customers and the world. I’ve heard claims that the PBC designation indicates management doesn’t care about profits. That’s categorically false. Management absolutely cares about profits and has repeatedly said so. I take them at their word.

Why? Because they recognize the longevity and success of their company depends on the ability to fund itself. They’ve always said they intend to be a profitable business, and the unit economics support that claim. But instead of capturing profits today, they are investing to build out the market and capture share sooner rather than later.

This all may sound a bit utopian, but it’s not unfounded. A larger theme is at play, which enables the creation of this new business model. Satellites are a massively underutilized technology, and the industry is at a tipping point. Planet is one of the companies leading the charge.

A satellite revolution

Satellites are at a unique point in time. People have started to view them as computers, and develop them like computers. Early launch, rapid iteration in space, and continuous replenishment. New satellites are much more powerful than predecessors at the same cost — Moore’s Law now applies to space.

But while space is more open for business today, it’s no easier to operate in orbit than it was ten years ago; the same harsh environment exists. Planet’s success comes not just from the founders’ early recognition of a changing order in space, but the company’s ability to execute — to build something new and valuable.

Planet sees the demand for its data, recognizes the longer-term opportunity, and is scaling investment rapidly. In the end, I expect this proves a smart tactic. If the market really emerges, and I very much think it will, a land grab will ensue. They’re in pole position to win this land grab, especially in electro-optical sensing. Hyperspectral is on its way, and if Planet executes the Tanager program well, it could very well be a winner in that market as well.

I find it an interesting and useful exercise to speculate about the future of the satellite data industry. There is little doubt the end state is a multi-sensor, near real-time network with a variety of winners. But what determines those winners? Where does the market segment?

One theory of mine is that each type of sensor (electro-optical, hyperspectral, SAR, AIS, ADS-B, radio occultation, etc.) will form some kind of duopoly. We know data lends itself to this market structure, so it would make logical sense. I also expect many of the winners to operate horizontally across several different types of sensors. There are natural synergies to operating across multiple domains in space.

I don’t know the future any better than you do, but it’s a viable outcome. More importantly, I think the total level of demand for data produced by these sensors will take the market by surprise. In many ways, Planet is a category bet just as much as a company bet; it will naturally benefit from growing consideration of satellite data for years to come, regardless of the eventual end state.

Recent struggles

Planet’s recent struggles are revealing. Obviously, sales execution could improve. But the interesting takeaway is how the unique horizontal application of its data across industries and use cases created the problem in the first place.

A wide variety of customers want the data, and many use it in disparate ways. This makes it difficult to standardize products and scale a sales motion. By focusing on a few core verticals now — civil government, agriculture, and defense & intelligence — Planet can start to develop more of a solution set.

It’s still working to reach other customers through an extensive partner network; it’s simply trying to avoid diluting sales resources in the process. The sales organization is still pretty lean, having been assembled mostly in the last few years. The new self-serve option (with transparent pricing) on Sentinel Hub is also a way to reach these smaller customers without stealing sales resources.

Investments like Planetary Variables also support improved sales execution. Product-izing the data is key to streamlining the contracting process and expanding the market. SwissRe and AXA wouldn’t be customers today if Planet hadn’t built Soil Water Moisture. PG&E wouldn’t be a customer without Forest Structure. The Brazilian Federal Police wouldn’t be a customer without Road & Building Detection. The list goes on.

Building a repeatable sales motion is difficult in the first place; the product being data that has never existed before adds a layer of complexity. But Planet is adapting to the market’s demands while sticking to its long-term strategy of (1) build new space systems, (2) product / solution-ize the data, leveraging partners where appropriate, and (3) scale the sales team. All of this should contribute to positive outcomes over time.

Putting it together

Long-lasting companies are built on positive feedback loops. If growth doesn’t reinforce itself, it is inherently tenuous. Planet is a positive feedback loop beneficiary, with growth likely to endure for years to come.

A largely fixed cost structure means revenue growth translates into steady profit (free cash flow) growth over time. Today, the potential profitability of the business is obscured by a level of investment many doubt the wisdom of, but few take the time to understand. These investments are informed by customer feedback and are set to generate increasing returns over time.

At a roughly $325 million valuation (less than a third of its 2015 Series C, and less than 3x gross profit), Planet presents a compelling investment opportunity. The company faces zero near-term financial risk with highly asymmetric potential.

Keeping tabs on the thesis

To close, I’ll share how I think about monitoring the thesis. First, I think it’s counterproductive to keep too close an eye. Focus on major developments in the business, not the stock. Don’t get caught up in the weekly, monthly, or quarterly news cycle.

The dominant theme of this investment is that things will take time to play out. This is exactly what creates the opportunity. If everything was happening at once, the market would recognize it — and price it more accurately.

Follow the storyline each year. Listen to management’s commentary each quarter. There’s no need to overanalyze a single quarter’s financials — the entire valuation rests in the terminal value anyway.

I focus on three key metrics each year:

Net dollar retention rate: Indicates Planet’s success in executing on the all-important feedback loop. Over 100% is necessary. (Note that Planet reports NDRR in a weird way; the full-year number is what matters.)

% of customers with >1 product: Measures Planet’s ability to further embed its data into customers’ workflows. We want continued expansion, but it may depend somewhat on the pace of new customer adds.

Gross margin: Tracks the economic model is working. Upwards movement is a green light, but expect some variability with the upcoming deployment of Pelican and Tanager.

Of course, I also want to see a steady progression towards positive free cash flow. But the truth is, with $320 million on the balance sheet, I’m just not too worried about it. They’ve got a >3 year runway at LTM cash burn, and they could probably be cash flow positive tomorrow if needed. Let ‘em invest for now.

This article will enter the archive of Investment Ideas, actionable stock picks intended for multi-year horizons. The performance of every idea (updated monthly) is here. These are ideas, not advice. Do your own research. Don’t take advice from me. I own the stock.

PL 0.00%↑ — Price at publication (as of March 1, 2024): $2.25

How did you back into the revenue assumptions? Currently attempting to make a revenue build for my finance class but am struggling to.

I am long on Planet. Averaging at about 2.7. Will add more to do DCA. Plan to allocate 10% of my portfolio at least and for 10 years at least. Great article.