Sonos in Perspective

Like Roku is an operating system (OS) for a smart TV, Sonos is an OS for a smart audio system. The competitive environment and economic model, however, differ between the two. Sonos has a virtual monopoly in wireless home audio and makes money from hardware. Roku has competition in smart TV OS and makes money from advertising.

Why does Sonos have no real competition?

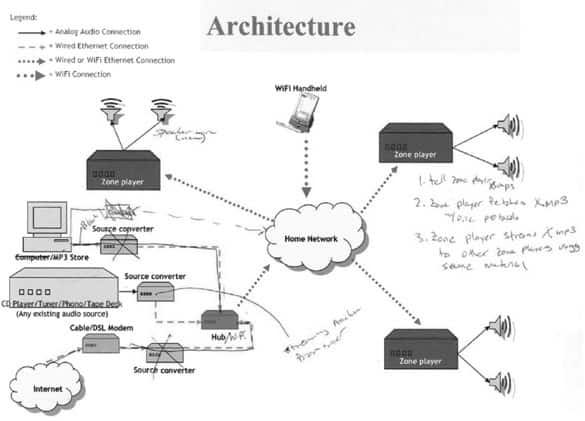

It starts with the fact that any audio experience is enhanced when multiple speakers work together. Years ago (prior to Wi-Fi becoming widespread), Sonos patented the networking architecture that allows speakers to communicate directly with each other over Wi-Fi, which allows the listener to synchronize audio and control multiple speakers from one place (the Sonos app).

Because Sonos owns the architecture, no competitor can offer a comparable in-home sound system (read: experience) as Sonos (hence why Sonos’ stated ambition is to be “the world’s leading sound experience brand.”) Make no mistake — Sonos competes with other brands, but they offer products; Sonos offers a system. Today, the system is mainly in homes, but the long-term opportunity is to expand into cars and commercial settings.

Unlike audio, there is little benefit to multiple TVs working together — you can’t really change the experience with a new architecture. Roku may have a superior OS, but it competes on the same dimensions as others.

Consumer expectations for audio and TV are also different. If Sonos put ads on its speakers, nobody would buy them. But nobody bats an eye at TV ads. As such, Sonos makes money on its hardware; it sells a premium product at a premium price. Roku makes money on advertising; it sells inexpensive hardware at roughly breakeven to create scale and feed its ad network.

Audio systems and TVs are also at different stages of adoption. Until the arrival of Sonos, multi-room home audio was reserved for ultra-wealthy audiophiles — a comparable in-home sound system would have cost $20-50k to install 20 years ago because of the wiring complexity. With no existing upgrade cycle for Sonos to tap into, it has had to build the market largely from scratch. Roku, on the other hand, can tap into the existing TV upgrade cycle (accelerated by the transition to streaming), and at an approachable price point ($25), it’s not too difficult a sale.

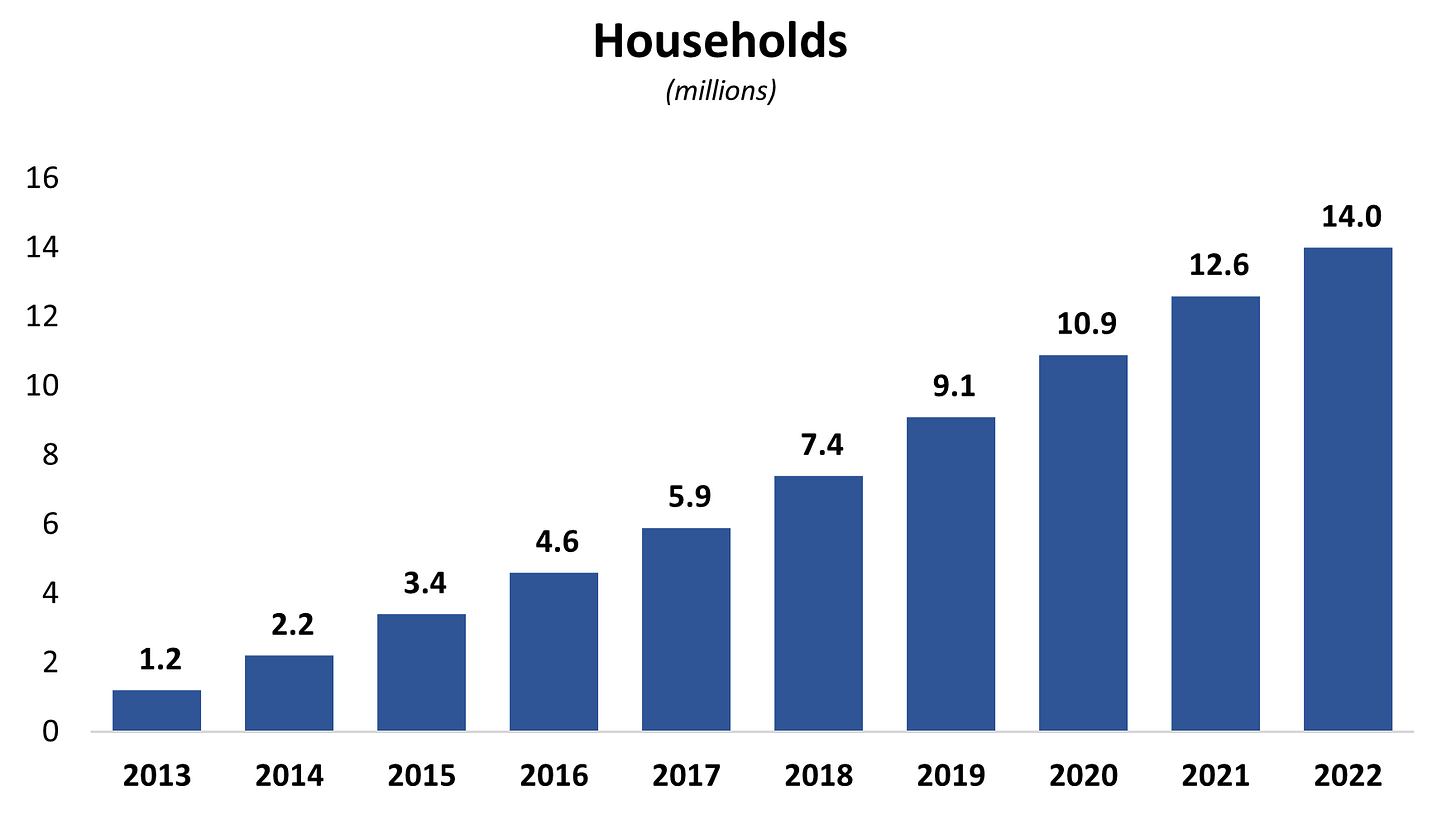

Both Sonos and Roku were founded in 2002, but Roku has ~5x the active accounts (households) as Sonos. Just six years ago, however, Roku had fewer accounts than Sonos does today. The purpose of this comparison is to frame the opportunity as Sonos sees it. Over time (perhaps a decade or more), it envisions tens of millions of homes across the world adopting smart home audio systems.

Much of Sonos’ historical growth is attributable to word of mouth (the #1 method of new household acquisition). When customers are your biggest advocates, it’s always a good sign. When those customers never leave, it’s a great sign, and when they buy more products over time, that’s how you deliver 17 consecutive years of revenue growth in an ultra-competitive industry.

In essence, that’s the Sonos flywheel: existing households bring in new households, and all households buy more products over time (and continue to spread the word to family and friends), creating a virtuous cycle.

The Hardware Story

A unique combination of software and hardware propels this flywheel. Most analysts question how Sonos can be the story of “software eats audio” if they don’t make money on software, but I think they forget the mechanics of audio. Engineering a real-life audio experience requires hardware. The software creates differentiation (a longer product life and the ability to act as a system) — which begets pricing power — but you can’t make money directly on the software when its value is in the experience. That’s the case at Sonos — and it’s quite similar to Apple, which still makes most of its money on hardware sales.

When analysts focus on the lack of recurring revenue, they ignore the legs on Sonos’ hardware business. The company owns its market and benefits from tailwinds in consumer habits and smart home adoption. More people have on-demand access to more music/podcasts than ever before. Remote work is a permanent fixture, meaning people are in their homes now more than ever. And people like to listen to music/podcasts. Sonos solves for the desire to have a convenient, high-quality listening experience anywhere in the home.

I think the demand for this type of experience is larger than people think, the market is far from saturated, and Sonos is primed to capitalize on it. Out of the 156 million affluent ($75k+ disposable income) households in Sonos’ core markets, it has <10% penetration today. Out of the 70 million with a Roku TV, Sonos has <20% penetration. Out of the 90+ million with a smart speaker, it has ~15% penetration.

Sonos has strategically positioned itself as the natural upgrade for those looking to improve on a base model Alexa (69% market share) or Google Assistant (25%) device. Internal studies from 2020 suggest ~80% of new Sonos households upgrade from an Amazon or Google device. The company has managed to construct its own upgrade cycle, and given smart speakers are still relatively new (<10 years since the first Alexa), the long tail of upgrades is quite attractive. Regardless of how you look at it, the hardware business has room to run.

Sonos has excelled at building and selling quality hardware for nearly 20 years, and the product leader (Nick Millington) has been at the company since 2003 (was instrumental in designing and patenting the original system). Since taking the helm in 2017, Patrick Spence has delivered on a target of at least two new products per year, which allows it to organically attract new households and steadily expand into new categories (such as portables and automotive recently).

To sustain this pace of product launches, Sonos doesn’t need to hire, which indicates the core profitability of the business is higher than most think. Headcount was essentially unchanged from 2017 to 2021 while revenue grew by more than $700 million. In 2022, headcount jumped ~20% (to ~1,800 employees), but this ramp makes sense in the context of 29% growth in 2021 and a long runway ahead (together with a balance sheet that can easily support it with over $400 million in net cash). Further, the business earns high returns on capital of ~28% in 2022 and ~41% in 2021.

Under the Hood: A Software Business?

Despite making money on hardware, Sonos resembles a software business. It iterates rapidly and ships new products consistently. Existing customers provide a sticky revenue stream (~40% of products sold each year), and their lifetime value is still growing. It operates with negative working capital. And it generates sales per employee on par with Roku and Microsoft, 2x its hardware peers.

Sonos — also like a software business — spends a significant sum of money to acquire new households. But as its presence grows, word of mouth spreads faster, and the necessity to spend to acquire households diminishes. We see this historically with sales and marketing declining from ~28% of revenue in 2013 to ~16% in 2022. This provides the financial flexibility to invest in R&D (to support new product launches and entry into new categories) despite gross margins significantly below most software businesses (but still above Apple’s!).

While Sonos continues to execute its hardware program, it can also experiment with service business models. I’d speculate most will fail or never reach the scale of hardware, but it’s not why I like the business — it’s optionality that adds upside if anything materializes. Here’s how Patrick Spence thinks about it:

We've been shipping hardware for 16 years. We know what we're doing on that front. We know what a good cadence of new products looks like, how they should work together.

When it comes to services, we're exploring, we're testing. We're trying some things, and we have ideas that we want to go out there. But it's just — it's super interesting because it's a different model than the hardware model where we need to determine every 18 to 24 months in advance exactly what we're building, and then we go and we work through it and have to bring it out and almost has to be perfect when it actually comes out, whereas we're learning this world of iterating quickly and testing new things in services and see what works and see what doesn't and then moving from there.

I think this is the right approach for the long-term.

I also think success in the hardware department (adding millions of households to the platform) will feed success in the software department. At scale, service business models are easier to build, and early attempts have already yielded some positive results. Sonos Radio is now the most listened-to service on the Sonos platform despite launching just 2.5 years ago. I would wager 99% of Sonos owners subscribe to Spotify or Apple Music, yet they still listen to Sonos Radio.

Sonos Radio’s success also exemplifies innovation — it built a new business (even if small) on top of its own platform after noticing people were spending nearly half of all listening time with radio content. Since it wasn’t a well-served market, Sonos built a solution. It’s not infringing on Spotify or Apple Music’s turf; it’s solving for a market demand and doing it well. That speaks volumes of the team and its approach to service experimentation.

Patent Risk

Much of Sonos’ future success will depend on the defensibility of its patent portfolio. The long-term story becomes murkier if you factor in competition for its niche. If Google somehow invalidates its patents, home audio will become a war with Amazon and Google, a shady proposition for a company 1/500 the size. Bose and others would also join the party with the same tech. Sonos competes with these players today, but as a system versus individual speakers.

I’m optimistic the patent portfolio will prove its mettle once again versus Google (two previous verdicts in its favor and a victory in ITC court now under appeal). But fighting a trillion-dollar behemoth is inherently uncertain. Despite the uncertainty, however, I view the legal proceedings against Google as further upside potential. Sonos has won every major ruling to date and previously won two licensing deals by taking competitors to court. How would the market react to a licensing deal from Google?

Conclusion

The term “flywheel” is overused. People hear “flywheel” now and think, “I’ve heard this story before — nothing new here.” But flywheel is overused for a reason — when it works, it works. At Sonos, it works, and has worked for the last 17 years. Little has changed in the competitive or consumer environment that leads me to believe the flywheel will slow or stop anytime soon.

If anything, just as Roku saw a dramatic acceleration over the last six years, Sonos may see its growth accelerate in the future as households who entered the smart speaker space over the last few years look for a better (privacy-oriented) experience. We’ve already seen some evidence of this: in the nine years since its first product launch, Sonos added just 2.2 million homes; in the eight years since, 11.8 million.

This is a team who has engineered profitable growth in the past and is committed to doing it again. (“We’re not in the business of growing OpEx in excess of revenue.”) The product pipeline is bustling. (“We've never had as many initiatives as we had today in terms of new products that we're going to launch in the future.”) And with plans to enter four new categories in the near future, we could start see the flywheel spin faster.

Analysts think of Sonos as an unprofitable consumer electronics business with a tenuous market position. I think it’s the opposite. With every product sold, it becomes more entrenched in the marketplace and accelerates its future growth. Patrick Spence is planning for a long runway ahead:

When my time at Sonos is done, I will judge our success by whether Sonos continues to grow and evolve forever. That is the bar that I hold myself and all of Sonos to.

With the C-suite steering the ship like a long-term owner (and doing a good job thus far), I’m content to sit back and see where we can go in 10 years.

SONO 0.00%↑ Thanks for reading. If you found it interesting, please subscribe or share with a friend.