Planet Labs: The Big Picture

How Planet Labs disrupted earth observation, upended the industry economics, and built a durable moat

Data is essential to decision makers. The desire to make better decisions fuels an ever-growing appetite for more (and higher quality) data. To meet this demand, new datasets are created (and added to) every day. Many of these measure, in some way, the activities of humans on the internet. We have little data, however, on the activities of humans on Earth. Planet aims to solve this problem.

A Look into Earth Observation

Earth observation (“EO”) uses remote sensors to measure elements (both visible and invisible to the human eye) on Earth’s surface. Different sensors produce different results, but the most common is a satellite-based telescopic camera capturing an image, from which data is extracted via the pixels. This article focuses on this method: what is known as optical EO.

The roots of EO date back to 1858 (shortly after the invention of photography in 1826) when Gaspard Felix Tournacchon took pictures from a balloon and sold it to the French military. Years later, the invention of the airplane made aerial photography common, and it served an important function throughout World War I and World War II.

Following WWII, aerial photography gained altitude with the first image from space taken by a camera strapped to a confiscated German V-2 rocket in 1946. To recover the images, the camera was enclosed in a steel cage for protection from the fall back to Earth.

In 1957, the launch of Sputnik-1 by the Soviets catapulted the world into the Space Age. During this period, governments deployed increasingly advanced technologies to explore the possibilities of space and ensure any advantages could not be exploited by rival nations. However, long, expensive development cycles, high launch costs, and regulation prevented the business from attracting commercial entrants.

This changed in 1993 when the Department of Commerce granted WorldView Imaging Corporation (later DigitalGlobe, now part of Maxar) the first license for a private enterprise to build and operate a commercial satellite EO system.

The early days of commercial satellites were a struggle. In 1997, the company lost contact with its first satellite, EarlyBird-1, after only 4 days of operation. The second satellite, Quickbird-1, launched in 2000 but never reached orbit. The third time proved to be the charm in this case as DigitalGlobe launched its first successful satellite in October 2001.

Throughout this period and the ensuing decade, satellite development exhibited a pattern: build larger, more expensive satellites to take higher resolution images, at lower revisit times (the time between two images of the same spot). This was only natural, as operators were incentivized to cater to the largest buyers — governments (~75% of the market) — who demanded exactly that.

The pattern is evident in the progression of Maxar’s WorldView satellites (which can be used as a proxy for the industry’s early years):

WorldView-1 (launched September 2007)

3.6m x 2.5m x 7.1m; 2290 kg; 50cm resolution; 1.7 days revisit

WorldView-2 (launched October 2009)

5.7m x 2.5m x 7.1m; 2615 kg; 46cm resolution; 1.1 days revisit

WorldView-3 (launched August 2014)

5.7m x 2.5m x 7.1m; 2800 kg; 30cm resolution; <1 day revisit

This approach, however, was prohibitively expensive; WorldView-1 and 2 cost around $900 million while the WorldView-3 program cost around $650 million. As a result, innovation faltered and the high costs of procurement limited expansion into commercial buyers. Further, the failure of WorldView-4 (launched in November 2016, decommissioned in January 2019) exposed the fragility of a business model dependent on transactional revenue and building few, high-performance satellites at exorbitant cost (more on this later).

The Birth of Agile Aerospace

Beginning in the early 2010s and continuing today, the development model shifted. Planet pioneered a new approach: build smaller, cheaper satellites with comparable performance to traditional large buses (a bus is the main body of a satellite) at a fraction of the cost.

Two major changes fueled this shift:

1,000x increase in cost-performance of smaller satellites, driven by the proliferation of advanced commercial off-the-shelf (“COTS”) electronics.

4-10x decline in launch costs (varied based on provider), driven by SpaceX’s invention of the reusable rocket.

These improvements enabled satellite operators to tolerate the one thing they previously could not: failure (also a necessary ingredient for innovation). This novel approach, modeled after the frequent iteration and rapid release of agile software development, became known as “agile aerospace” and has driven a sustained acceleration in the pace of innovation.

So, where did the industry go from here? The “new space age” for EO remains in relative infancy. Thus far, most commercial entrants — including many of Planet’s contemporaries — have failed or underperformed expectations, whether due to technological challenges or a lack of capital. For those new operators who have stood the test of time, they remain in the early stages of building a sales motion and bringing the data to market. Planet’s success to date, however, is a testament to the functionality of the new technology and the value of the data. Now, we enter the process of discovering the data’s true value to commercial and government customers.

Zooming Out

Broadly speaking, the cost of experimentation in EO continues to decline as the commercial (and government) market expands. This sets the stage to unlock the long-term market opportunity. Estimates peg the market for global satellite EO data at somewhere between $3.5 to $5.5 billion in 2021 with future growth rates in the ~7-10% range. The trouble with these estimates, however, is they likely fail to account for the impact a disruptive technology has on the market. No one correctly predicts the market size of a disruptive technology because no one can precisely anticipate the incremental value created for customers.

My contention is demand for EO data will substantially pick up over the next decade as the addition of software enhances its utility. Rarely do industries experience the magnitude of change in performance capability that Planet has achieved without a corresponding change in market growth or market share. Satellite imagery is already more widely used than ever, but it remains far from mass adoption because of a lack of accessibility – most use cases still require geospatial experts to interpret the data. Planet is addressing this problem by “moving up the stack” (turning raw imagery into actionable analytics), thereby making it accessible to ordinary users.

Looking ahead, I find it a simple exercise to conceive of a world where a daily, global dataset of Earth imagery accompanied by industry-specific analytics is valuable to thousands of businesses. Planet, with an unmatched constellation and platform, is best positioned to lead this market.

The Disruptor

Planet Labs is the second largest commercial satellite constellation operator behind SpaceX (Starlink). The Company has designed, built, and launched over 450 satellites and currently operates a constellation of over 200 satellites orbiting the Earth every 90 minutes (known as PlanetScope). These satellites continuously monitor the Earth, capturing 300 million square kilometers of imagery (2x the Earth’s landmass) at 3.7m resolution every day. The PlanetScope constellation consists of Dove satellites, which cost ~$300k (about 50% materials, 50% labor and launch) and serve a useful life of ~3 years. The payback period is estimated to be 3-6 months.

It also operates a SkySat constellation, consisting of 21 high-resolution satellites that offer a more traditional tasking service where customers can “zoom in” on a specific area at higher resolution (50cm). This constellation is undergoing an upgrade and will be replaced with Pelican satellites beginning in 2023. Pelicans offer higher resolution (30cm; equivalent to highest commercially available) and faster revisit rates (up to 30 per day versus 10 now). A successful launch of Pelican will also represent a remarkable achievement in reducing latency (the time from when an image is taken to customer delivery), from hours to minutes. Pelicans are larger and more expensive than Doves — costing around $4-4.5 million — but cheaper than legacy SkySats. They serve a useful life of ~5 years.

The two constellations operate in complementary fashion. PlanetScope functions as a daily global scanner. Each day, it images every corner of the landmass. When change is detected, a customer can automatically task a high-resolution satellite without human contact, reducing friction and the time to information receipt.

Throughout this process, Planet is building a valuable archive of imagery data. Essentially, Planet is compiling millions of inputs (the historical data), along with the associated outputs (the current data). Armed with this volume of raw data, predictive analytics and a host of other valuable services become a fundamentally simple, but technologically complex, math equation.

The Business Model

Planet generates revenue by selling licenses to its satellite data via annual subscriptions (average length of ~2 years) to its cloud-based platform. Subscription pricing depends on coverage area, the number of users, and the depth of analytics (how far up the software stack).

The company’s customers consist of both government and commercial customers. Defense and intelligence agencies comprise ~34% of revenue while civil governments account for ~24% as of fiscal Q3 2023. Commercial buyers represent ~41% of revenue and span the agricultural, forestry, mapping, and insurance industries. Over time, management anticipates a large market for the energy and finance industries as well.

Company Values

Importantly, Planet is a mission-driven company. The founders (two of three remain at the company; the third left in 2015 for venture capital) started with an idea to count every tree on Earth, then executed the idea through a first-principles approach — what would it take? A constellation capable of imaging the whole Earth daily. Now, they are exploring the commercial opportunities enabled through the idea.

Further, it’s vital to understand disruption is in the company’s DNA. The initial idea was impossible to execute under a legacy EO model. To make it economically viable, the founders threw out the traditional industry playbook: sell expensive images, taken from high-resolution satellites, to high-paying governments on a transactional basis. Instead, Planet built hundreds of medium resolution satellites that took millions of images each day, then sold each image an unlimited number of times via subscriptions. In doing so, Planet lowered the boundaries to access while building out two revolutionary capabilities: global scale and a time-axis for EO data. These capabilities hold strong potential as they are uniquely complementary, have never been accomplished, and enable the precise measurement of human activity on Earth.

The Competitive Advantage (“Moat”)

In building out its capabilities, Planet has constructed a moat that compounds with every day competitors lack a comparable constellation. No one can offer the data (information) Planet gathers daily. It will be years before anyone can replicate the raw data collection system, without consideration of the software on top (which delivers the real value). Let’s examine exactly how difficult it is to replicate Planet’s capabilities.

First, it’s important to understand the scale of Planet’s 200-satellite constellation imaging over 300 million square kilometers daily. Maxar, the largest commercial EO firm, operates four satellites covering 3.8 million square kilometers each day. Satellogic, a firm founded prior to Planet with similar aspirations, operates 26 satellites covering 7.8 million square kilometers per day. BlackSky has 14 satellites covering ~29k square kilometers. Airbus operates 16 satellites that collectively “cover the Earth every 26 days”. Planet covers more than 40x the area of its closest competitor daily.

But replicating Planet’s constellation does not only require coverage of the entire Earth landmass; the constellation must produce a uniform data series from the imagery. In practice, this means the image must be taken at the same angle, covering the same area, every day. Obtaining the raw imagery is just the first step, however, as the data must then be processed and stored for machine learning, a difficult task when dealing with geospatial data.

Ultimately, Planet has built out an unparalleled systems engineering capability covering satellite research and development, mission operations, data processing, and over time, analytics. It is a formidable technological feat that took Planet over six years to tackle with a singular focus. Most competitors lack such a mission-driven, singular focus, which could be why several firms founded around the same time as Planet have fallen short of expectations.

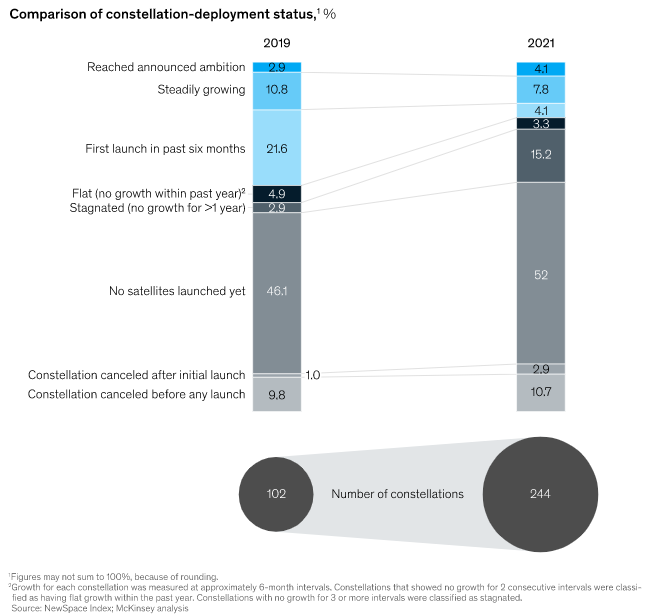

A recent McKinsey report offers data on precisely how many failures there have been. Despite a significant increase in the number of commercial constellations announced, execution has been lacking: 96% of constellations announced prior to 2019 have not reached their announced ambition, while 65% have either not launched a single satellite or canceled their plans.

Beyond the technological hurdle, any attempt to replicate Planet’s constellation will require access to a significant amount of capital. Amid the growing uncertainty in capital markets, this could present a meaningful obstacle.

The Compounding Effect

As the first mover, Planet can build software on top of its proprietary dataset to address new use cases. Thus far, commercial use cases are mostly limited to industries with geospatial data expertise (governments, agriculture, and mapping for example). While competitors work to obtain the requisite scale of data gathering, Planet can focus on the next monumental technological hurdle: developing object recognition algorithms (as part of its mission to index the Earth) and predictive analytics (to expand the addressable market). By the time any competitors launch a functioning constellation (at least 3-5 years, by many estimates), Planet will have had the opportunity to develop functional analytics to address a variety of industry use cases.

This first-mover advantage extends to the application ecosystem and customer interaction. As the only company to produce an EO dataset at global scale (with a daily time axis), third-party developers are incentivized to build applications on its platform. Further, the Company’s product development benefits from customer input. Planet can engage with customers to determine which sensors should be added to the next generation of satellites to satisfy a market demand, which analytics should be developed first, and importantly, which products are profitable.

In addition, Planet’s archive of 2,000+ images of every point on Earth’s landmass are data essential to training its machine learning models. Competitors cannot go back in time to capture this imagery.

The Financials

One of the most unique aspects of Planet is its business model. Instead of only capturing highly valuable imagery requested by a government or large customer, Planet takes an excess of images every day and licenses each image via annual subscriptions (average of two years) to any customer who asks for it. This results in a scalable platform with a high degree of revenue visibility (93% of revenue is recurring) and greatly improved unit economics at scale.

The world “scale” is key here, as revenue growth is the necessary condition to unlock Planet’s potential. Direct margins are estimated to be 95%+ as the cost to obtain imagery is largely fixed. The impact on profitability is clear, with gross margins increasing 1290 basis points year-over-year.

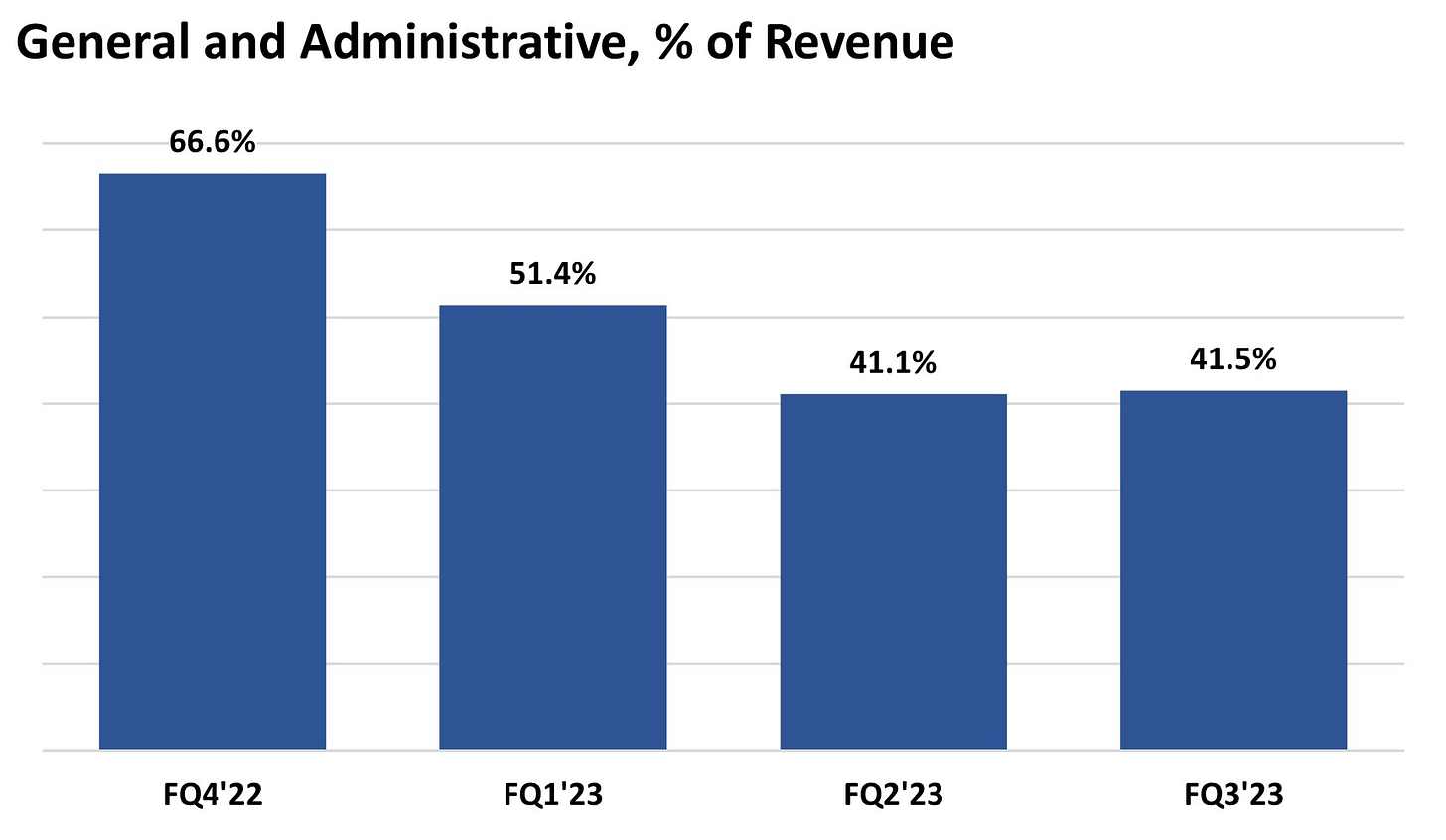

Planet also demonstrates operating leverage despite a sharp ramp-up of investment after going public. All three categories of operating expense have declined as a percent of revenue over its brief history as a public company.

It’s important to analyze profitability in the context of its public debut because management has often cited a lack of capital as the primary constraint to revenue growth. After receiving this long sought-after growth capital, the company sharply increased investment in FQ4 2022. Since then, results speak for themself. Revenue growth rapidly accelerated, providing evidence of the potential for significant profitability at scale. In each of the last three quarters, management has increased full year revenue guidance and beat analyst estimates.

To sustain this level of growth, Planet must continue to solve for new use cases while serving existing customers in new ways. Its record in both departments is quite strong, as evidenced by consistent growth in customer count and net dollar retention rate (“NDRR”).

Customer count has increased for 14 consecutive quarters, exhibiting a 27% 3-year CAGR as market awareness has spread and industry adoption has improved.

NDRR – a gauge of Planet’s ability to provide incremental value to customers – has also been strong, reaching 125% in the most recent quarter. Importantly, this metric is calculated based on the annual contract value (“ACV”) at the start of the fiscal year, while most companies report it on a Y/Y basis. If Planet were to report a year-over-year metric, it would be meaningfully higher.

Perhaps the most important aspect of Planet’s business is the built-in pricing power, deployed through a “land and expand” customer strategy. Once a customer joins Planet’s platform and uses its data, Planet offers more in-depth analytics on the customer’s area of interest. These analytics come with contract expansions, and over time, the customer spends more while its workflows become more embedded on Planet’s platform. A strong and growing NDRR provides proof of this pattern.

Runway for Growth

Focusing exclusively on agriculture, it appears there is plenty of room to run. Agriculture covers ~25% of the Earth’s landmass and contributes ~$12 trillion to the global economy each year. Planet is the only firm capable of monitoring the entirety of this farmland, and the use of Planet’s data is proven to improve crop yields by 20-40% and lead to more accurate forecasts. The scale of agriculture in the context of Planet’s $157 million of 2021 revenue implies the company remains far from capturing the full value of its data.

The economic value of Planet’s data is great; the challenge is reaching all the relevant parties. The real market opportunity long-term is in the customers who don’t see the data; those who interface exclusively with the data outputs, which are generated automatically and integrated into their day-to-day workflow. When (or if, depending on your confidence) this becomes a standard offering, I imagine Planet will be multiples of its current size.

Management

At some level, every investment can be boiled down to a bet on the people behind the company. At Planet, the people are perhaps the most exceptional asset. The co-founders, Will Marshall (CEO) and Robbie Schingler (Chief Strategy Officer), are passionate space geeks who successfully executed an ambitious idea to image the whole Earth every day after growing frustrated with the difficulty of innovating at NASA.

Marshall is the visionary face of the company, responsible for building the team and product. Schingler is the brilliant businessman, the mind behind the EO subscription model and likely the man to drive the future evolution of the industry’s economics. Listening to the two share thoughts on the future evolution of commercial EO, it’s difficult not to draw comparisons to internet visionaries’ founding ideas.

The two worked at NASA for years, and Marshall (along with the third co-founder, Chris Boshuizen) devised the first innovative application of COTS electronics in satellites, PhoneSat (it is exactly what it sounds like). But, when the trio’s commercial satellite development ideas differed from NASA’s mission, they spun out to form Planet (initially known as Cosmogia). Far from the “clean rooms” of satellite companies, the team adopted Silicon Valley tactics, building the first satellite in the garage of a house the two were living in.

Overall, the management team exhibits several characteristics I hold in high regard.

Alignment: Will Marshall owns 9.0%, and Robbie Schingler owns 8.2% of the company.

Competence: I believe competence largely speaks for itself in building out the constellation and bringing a new dataset to market, but it’s nice to see execution has been better than ever recently. After exceeding projections for FY 2022, the company is on track to meet or exceed projections for FY 2023, outlined in July 2021 as part of the initial SPAC presentation (to justify a $2.8 billion valuation).

Transparency: After the SPAC completion, management opted to report earnings for FQ3 2022, although it was not mandated. After receiving the EOCL contract, management only reported the firm commitments, leaving the potential upside out. I consider this a meaningful boost to credibility. Planet also hosted its first Investor Day in October, less than a year after going public. Although not critical data points, I prefer a management team who engages with shareholders and thinks like owners.

To summarize, management is the strong point of the business. They are passionate, capable operators focused on the long-term opportunity.

Risks

This piece could pass as sales material thus far, but I assure you there is no shortage of uncertainty, as with any company. That said, I do not believe the principal risk for Planet is the financial situation, satellite performance, geopolitical issues, or even competition. The principal risk is that as it continues to accumulate data (from more satellites with more sensors) and layer algorithms on top, the commercial value of the data does not increase. In other words, either the data doesn’t have much inherent value, or it becomes commoditized. It’s a difficult concept to analyze, but asking, “what is Planet’s data?” can help to put it in context.

Planet’s data is the entire Earth landmass, broken down into 3-meter pixels measuring a variety of elements invisible to the human eye. To me, that seems to describe something with inherent value, and there are many customers spending millions who agree. And, as outlined above, given the difficulty of replicating the constellation, the chances of it becoming commoditized over the coming years are virtually zero.

The company does remain unprofitable and will continue to burn cash over the next few years while it ramps up investments into software and sales headcount. I don’t think this will pose a material problem as Planet holds zero debt and ~$425 million in cash compared to a ~$33 million burn rate in the most recent quarter.

Satellite failure or underperformance may also present a risk, but a closer look reveals this is actually a strength of Planet’s business relative to legacy EO companies. When Maxar’s WorldView-4 failed, the company’s ability to serve customers was impaired. Planet, however, builds redundancy into the constellation (it covers the Earth’s landmass 2x per day), preventing failure from destabilizing the product. If several satellites were to fail, the core service would remain largely uninterrupted.

What about countries that don’t want to be imaged? Can Russia or China shoot down Planet’s satellites to avoid being observed? While they certainly can, I don’t think they will, as dictated by international law. The Outer Space Treaty, signed in 1967 by the United States, United Kingdom, and Soviet Union (now covering 135 countries), prohibits any nation from claiming territory above 100km altitude. Planet’s satellites orbit at ~400km, well above the protected range.

And finally, the PlanetScope constellation produces optical imagery data, which doesn’t work at night and can be obstructed by clouds. Several firms, including Terran Orbital and ICEYE, have announced plans to build synthetic aperture radar (“SAR”) constellations capable of imagery at night and through cloud cover. However, I believe the commercial opportunity for SAR data will remain limited by the high cost of procurement – SAR satellites cost significantly more to build, and the associated data costs more to process. It’s unlikely most commercial buyers will make the jump to such costly imagery when the primary barrier to market growth historically has been cost.

Conclusion

Planet is in the early stages of making EO data accessible through scale and software. It pioneered a new form of satellite development; designed, built, and launched a revolutionary constellation; and transformed the economics of the industry. In the context of these accomplishments, the company’s next mission – to index the Earth and make it searchable – appears feasible. The possibilities enabled by such a “queryable Earth” are nearly endless. Planet has built the platform, and the team, to do it.

- Gallagher

This is really well done. Great work and thx for sharing!