If you would prefer to read in PDF format, click below.

Last month, we revisited my thesis in Planet, Xometry, and Pagaya. This month is a bit limited – a vacation and an incredibly busy time at work will do that to you – but we’ll take a quick tour of earnings at Thryv and Upstart and close with a brief analysis of Planet Labs’s launch strategy and capital efficiency. March should be a more productive month.

Feedback is always welcome. Disagreements are encouraged. And as always, thanks for reading. If you find my work useful, please consider sharing with a friend.

1. Thryv | THRY

Context

I’ve followed Thryv for almost two years now, owned a small position for just over six months, and will likely size it up in the near future. I look forward to the Thryv earnings call every quarter for a refreshingly simple explanation of where they’re going, how they plan to get there, and what they have done most recently to execute on that plan.

This is the first time I’m writing about the company, so let me add some context. I own Thryv because it’s a good product and a good business model, addressing a massive market opportunity, and led by a uniquely qualified and talented management team. If I could boil my investment down to one factor, it’s Joe Walsh. I have a tremendous amount of trust in his ability to create a successful outcome for shareholders in the long run.

The stock is generally held down by a legacy print directory advertising business (better known as the Yellow Pages) which, as with all publishers, has been devastated by Google and the internet more broadly.

When valuing the company, I prefer to ignore this print advertising business, though it should throw off enough cash to eliminate the debt by the end of the decade. What I see is a profitable, almost $500M software business that should grow steadily north of 20% and deliver ~20% free cash flow margins at maturity. It’s a well managed operation, led by a group with a history of delivering results.

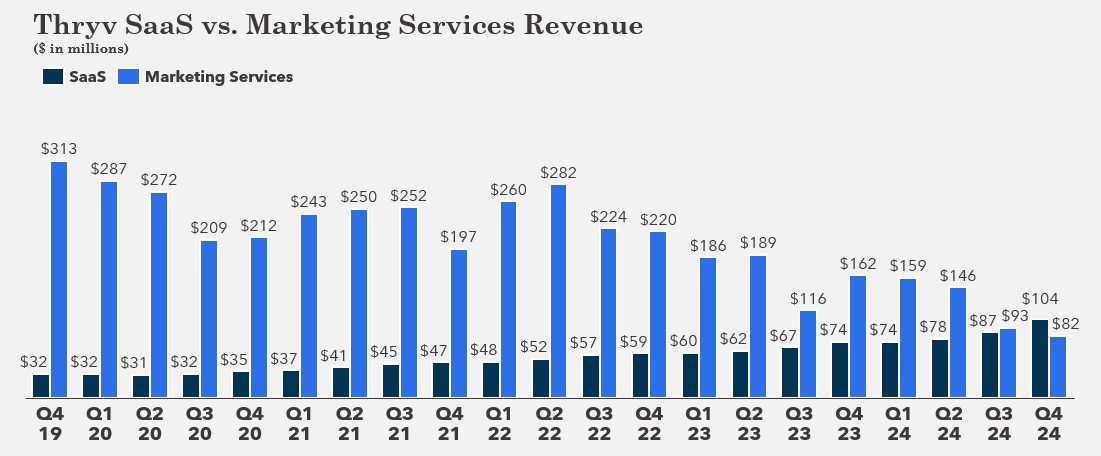

Q4 2024 is technically an important quarter as it is the first time software revenue eclipsed the legacy print advertising business.

That said, the overarching story is little changed. Thryv continues to deliver profitable software growth while building out its platform and further penetrating an expansive legacy customer base with new software solutions.

Q4 2024 Earnings

The big news surrounding Thryv recently is its acquisition of Keap. The rationale for the deal was straightforward: Thryv’s bread and butter is lead generation, and Keap specializes in lead conversion. In short, Thryv’s marketing offering just got a whole lot more effective, and what’s good for customers is good for the business.

A few other components of the acquisition are (1) the addition of a scaled partner channel motion and (2) a significant increase in development capacity.

Thryv met limited success in its attempts to build out its own partner channel, but Keap brings 1,000 certified partners and a sales motion more than two decades in the making. Thryv excels at selling directly into small businesses, or more specifically upgrading its large base of legacy print advertising clients to its new software solution, but the partner channel broadens the GTM substantially and allows it to reach slightly larger businesses.

Development capacity is a constraint for any technology business, and the Keap acquisition added 100 experienced product and engineering employees, growing the existing team by 50%. Joe Walsh is excited about the potential here, which means I’m excited about the potential as well. We could see an increase in velocity that allows the company to more quickly realize its vision for the platform.

On the call, Walsh highlighted that in just a few months of ownership, they’ve realized $10M of cost synergies. The greater opportunity, however, lies in cross-selling Keap’s lead conversion products and Thryv’s business management software across the combined customer base. All told, management expects this effort to generate $50M of incremental revenue in the next three years: ~$5M this year, $20M next year, and $25M in 2027.

This cross-selling effort, though in the early days, should support an increasing emphasis on ARPU growth in 2025, though by no means is it the only vector of improvement:

“I think we spent the last couple of years really building a very big client base… and I think what we want to do now, and what we're asking our sales organization and our marketing team to do, is really spend time with that installed base and make sure that they are engaged with the product, bedded down, using it and that we're meeting more and more of their needs… And so not to be crass, but upselling them, basically working with them to get more products in place… I think this year, '25 will be a year where that's a beacon.”

I like this focus. Spending more time with existing customers not only contributes to ARPU growth but also holds down churn. And churn can be dangerous in the ultra small business segment where Thryv operates today – as the company readily knows from the early years of its foray into software.

ARPU growth has lagged as new customer additions have accelerated significantly over the last year. New users tend to start with a single product, but as they further build out the platform and move slightly up market, ARPU still has lots of room to run. On average, Thryv still costs around a third of Hubspot annually.

Importantly, moving up market does not mean leaving the space where Thryv has an edge in product simplicity. The company has no plans to serve larger industry players or even compete with the mid-market Hubspot; they want to serve more of the local service industry owner-operators with “five or six trucks” as opposed to one or two. That segment, however, requires more features. To meet this need, Thryv launched Reporting Center, a platform console that offers users a consolidated view from which to manage the business.

On the platform topic more generally, I want to highlight this quote from the call:

“As far as additional centers going into '26 and '27, we've stopped short of promising any further centers. Now that doesn't mean we won't add any, but what we are going to be really focused on is making it all really work well together, making sure the platform of tools that we have is interoperable with other things in the market… The UIs are integrated. Everything just works well. We're not looking for Frankenstein here. We want a really easy-to-use platform. One of the things that you're dealing with very small businesses, you have to make it kind of consumer grade. It's got to be really simple and clear. You can't challenge people with hard-to-use tools.”

Again, I like this focus on how the end customer actually interacts with the product. Software is built to save people time, and a small business owner’s worst nightmare is spending a lot of time training people to use a new tool. Once the core features are in place (which they should be in a year or two with the impending launch of Workforce Center), it’s more important that everything work well together than to have more powerful features. Powerful features are geared towards a more sophisticated customer segment.

In fact, I think a common trap is building too much and, in doing so, introducing new complexities that abstract the core problem you are solving from the main view. Thryv is keeping the main thing the main thing, which is important to their success long term and a reflection of the team’s experience in serving small businesses.

This quarter is just another step in the right direction. The customer base is growing significantly as the company accelerates its move to upgrade legacy clients. More importantly, millions of small businesses outside the current universe still have yet to make the move to the cloud. Net dollar retention remains around the 100% mark. ARPU growth is in the pipeline with the maturation of existing centers, ramp up of new centers, and penetration of add-on products such as those offered by Keap. There is a lot more wood to chop, and I think Thryv has the DNA to get it done.

2. Upstart | UPST

Context

Investors love predictability, and Upstart is anything but. You have to accept a certain amount of volatility – both to the upside and downside – if you invest in Upstart. I can’t think of many companies whose revenue has declined 30% over the last two years yet still compounded at 32% annually over the last five years.

I own Upstart because (1) I think the fundamental technology thesis behind its founding will prove out over time, (2) the unit economics are solid, (3) the market opportunity is enormous, and (4) I have deep trust in and respect for the management team.

The underlying thesis rides the same wave as my thesis in Pagaya: AI will inevitably disrupt credit, and its deployment will come from AI networks who match banks and other capital providers with varying risk tolerances to borrowers with varying risk profiles and, in doing so, construct a real-time database of actual consumer creditworthiness. As this database grows, early movers such as Pagaya and Upstart will benefit from network effects that allow their models to get smarter, which will allow them to extend more credit and deliver a more compelling value proposition to both borrowers and capital providers.

Great companies focus on making consistent, incremental improvements to their core business engine in pursuit of a mission that results in a large market opportunity. In Upstart’s case, the engine is a collection of AI models capable of sourcing, verifying, underwriting, and servicing borrowers in an end-to-end automated manner. Its mission is to improve the accessibility and affordability of credit for the masses.

Such a mission introduces extraordinary challenges as credit is one of the oldest, largest, and most cyclical industries in the world. But while the last two years have laid bare the impact of such cyclicality, Upstart has continued to make improvements to its engine. Now, as it begins to emerge from the cycle, those improvements are beginning to manifest in the financials.

The building blocks of Upstart’s engine – its AI system – are the features / variables used to assess creditworthiness (likened to columns in a spreadsheet), the actual repayment data (rows), and the algorithms that identify patterns among that data. Since the beginning of 2022, when Upstart entered this cycle, it has increased the number of features by ~67% (including incorporating APR, which drove a step-function improvement in model accuracy) and gathered almost 4x the amount of repayment data across time.

The data corpus is significantly larger today and the algorithms significantly better at predicting the default risk for an individual. To successfully replicate such a system, you have to solve a time series problem – you can’t just build a better model without learning how certain risk factors influence the creditworthiness of a borrower. Learning that requires actually extending credit to various borrower segments and observing the repayments over time.

Upstart has a significant lead in understanding these risk factors’ influence on actual creditworthiness, and not many people are pursuing a similar strategy. Dave Girouard shared a particularly interesting quote in the most recent earnings call (emphasis mine):

“One of our very early Upstarters who went on to join Google's DeepMind and then eventually started his own AI venture fund said something recently that stuck with me. ‘Upstart is building the foundation model for credit. Nobody else is even trying.’

This is a simple yet elegant description of Upstart. In fact, I wish I had said it. But if you're a believer in the transformational power of AI, it's undeniable that the trillions of dollars of credit origination each year represent a clear and obvious opportunity for AI to improve the lives of people everywhere.

Competition among foundational models is fierce and includes highly capable open source models. Upstart’s moat is the proprietary nature of its models, the compounding learning inherent to such machine models, and the difficulty one would have to overcome to replicate the core credit decisioning model, let alone the end-to-end conversion funnel. Upstart is a logical choice to bring AI lending to the mainstream, and the reward for doing so will be massive.

Q4 2024 Earnings

Upstart appears to be back in growth mode entering 2025. After growing fee revenue 13% and contribution profit 8% in 2024, 2025 guidance calls for 45% fee revenue and 37% contribution profit growth. We know from history that Upstart can grow extremely rapidly when the environment is accommodating, so it will be interesting to track how sequential growth rates stack up in 2025.

Upstart’s organizational focus is one of its clearest differentiators. Everything is about a simple mission: delivering the best process and the best rate to every loan applicant. I like how Dave Girouard framed the day-to-day activity of the company on the Q4 call:

“Most of what we do here are just fundamental improvements to risk separation and automation, and those deliver growth. So I think we'll just take the macro wins when we can get them, and otherwise, we will keep cranking away on more accurate models.”

The business is obviously dependent on macro to a certain extent, but the people focus on what they can control, and the past few quarters are evidence that alone can get it done. 2022 and 2023 were anomalies in terms of the speed of rate hikes followed by the rapid increase in defaults among lower income borrowers and, later, higher income borrowers. As those impacts subside, Upstart will be a beneficiary of both an improving macro and a significantly improved business engine.

Upstart’s aim to be the fastest to react to macro rather than the earliest to predict the macro is a good strategy, and it’s clear they have made progress in the department. Girouard shared that, had their current macro tools existed during the prior period of volatility, they would have avoided 55% of excess defaults and returned to full calibration (the difference between predicted and actual default) 12 months earlier.

One analyst asked a rather interesting question about how long it might take to return to the prior peak conversion rate and loan origination volume. Sanjay Datta’s response, though lengthy, is worth unpacking:

“The path back to that scale of business – I mean, the obvious answer is a drop in the risk of the environment. I guess you could sort of proxy that with a drop in the UMI. But I also think that the path back will look different than our original path there because, compared to that time, our models are dramatically stronger.

A lot of that is not obvious because of the high rates and the high level of risk in the environment, so as Dave said, prices are still quite elevated. But the models themselves, in terms of their ability to decision risk between relatively similar-looking borrowers, are dramatically better. And so I think we will not require as constructive an environment as existed in 2022 in order to get back to that rough level of scale.

And maybe a related point is that, as and when we do, our business model itself is much stronger. I think we've been clear that we do not believe our contribution margins will fall back to the level that they were back then. I think we're much more optimized in how we price and how we measure elasticity and how we manage our take rates. And so I think, again, for a similar size of top line business, you should expect us now to have better margins and frankly, a more streamlined fixed cost base.

The only real difference beyond that is the fact that we have undertaken a few bets that are more early stage, and we expect those to contribute over time as well, and there will be some period of time in which we have to incubate that. But beyond that, I think across the board, whether you're looking at our business model or the strength of our actual underlying technology, it's pretty much better across the board.”

Of course, macro tailwinds could accelerate growth, but what stands out to me is Sanjay Datta’s comment on contribution margins. He expects them to remain around the current level, even as they scale the business. That differs from Girouard’s explanation last quarter: “We expect our contribution margins to come back down to earth as our volumes expand.”

Datta could be signaling a change in tune, but realistically, I think it’s just a matter of the degree of change. They will inevitably decline somewhat, but maybe not to the full extent of what was expected previously. Either way, it should be an interesting dynamic to monitor moving forward.

Datta’s last sentence adds emphasis to my initial context, which is that while Upstart has had a difficult few years, it is undoubtedly a stronger company today from both a technology and business model standpoint. One of those technology areas is servicing.

On the Q4 2023 call a year ago, Girouard announced, “We've begun programmatically gathering the data that will unlock the type of efficiency and efficacy gain in servicing that we've long seen on the origination side.”

In the last two years, the servicing product and engineering teams have more than tripled. This quarter, we received some more confirmation that this investment is paying off. A few stats worth highlighting:

People-related cost per current loan fell 50% since the beginning of 2024

Roll rates from 1-day delinquent to charge-off are down 15% YoY

93% of new loans enrolled in AutoPay (highest level in two years)

Portfolio-wide, AutoPay enrollment exceeded 80% for the first time ever

As these investments in servicing continue to pay dividends into 2025, it may support improvement in the unit economics of each loan. Servicing and verification cost per loan bumped up in 2024, but the benefits of automation pay off disproportionately at a larger scale.

Another key dimension of the business is the “supply chain of money.” Lending partners are returning to the platform in significant numbers, with originations up 30% QoQ and 76% YoY. Higher credit quality products such as the auto loan and HELOC should drive more of this activity over time.

HELOCs have grown almost 4x over the last two quarters, and auto loans (both refinance and retail), after a long stretch of being stagnant, have grown over 3x since Q1 2024.

Committed capital partners upsized their platform commitments by $1.3B and have represented around 50% of the origination volume since Q2 2024. Upstart is a much more resilient business to external shocks now and is no longer funding-constrained. Growth should now come as a function of internal model improvements and automation – though any improvement in the macro will further bolster its results.

Upstart is a unique company pursuing a worthy mission and demonstrating real progress in its efforts. The unit economics are solid, and we even saw a countercyclical element in the company’s ability to flex take rates during a time of lower liquidity. In 2025, Upstart expects to return to significant growth and GAAP profitability.

All three co-founders remain at the company, along with a significant population of the early senior leadership team. They have survived numerous pivots to the strategy and business model and, each time, emerged a stronger company. Not much could happen in a single quarter to convince me the opportunity is lost, but this quarter has deepened my conviction that opportunity is large and ripe for the taking.

3. Planet Labs | PL

Launch Strategy

History fuels a company’s DNA, so I find stories, memos, or other details about the early years highly informative. This 2016 article by Mike Safyan, who has been at Planet since its founding and currently leads its launch strategy, is worth a read. One interesting takeaway is how the practical application of launch strategy has changed over time.

Planet is vertically integrated across satellite design and manufacturing, but a major dependency is launch – actually putting those satellites into operation. Long ago, Planet hired Chris Kemp (who later went on to co-found Astra) to explore the possibility of entering the launch business and concluded no. I think this was the right choice, and it indicates the focus of the business. Even if not in abundant supply, launch is a commodity, a highly capital intensive / risky business and, at least today, not a very good one either.

While there is a far-out risk that major launch providers decide to stop launching Planet’s payloads, jack up the prices, and/or replicate their business, it’s unlikely. I’ve become more and more comfortable with this risk and, in fact, barely consider it a viable outcome today. Nonetheless, this article explains how the company thinks about mitigating its dependency on launch providers.

Simply put, the strategy is diversification, or as Safyan says, “many eggs in many baskets.” Spread payloads across multiple manifests and multiple rockets to reduce the impact of any launch delays or mission failures. Sounds good in theory, but if we look at the last six missions, all have flown under the SpaceX banner. So much for diversification today.

More than cause for concern, I think this reflects a change in the operating environment. The article is from 2016, a time when a statement like “launch, to put it plainly, is risky business,” made much more sense. SpaceX is now an 800 pound gorilla, and failure is an anomaly at the organization.

Launch prices have not declined as much as widely expected (and may have increased in certain cases, at least recently), but my guess is Planet trades diversification for reliability. Why risk satellites on a less proven vehicle when you can virtually guarantee success with SpaceX? I’m sure there is a willingness to experiment on occasion, and Planet also keeps launch contracts with Rocket Lab (to the best of my knowledge), but frankly I’m not surprised to see SpaceX as the new default. They launched 90% of mass to orbit last year.

Moving forward, I’m interested to see how the advent of massively larger rockets, and potentially dramatically lower launch costs, (e.g., Starship) may change Planet’s strategy. A decline in launch costs does not directly translate to a decline in launch prices, but if Starship successfully lowers the cost to orbit by an order of magnitude, maybe half of that gets passed through to customers like Planet. With launch a significant input to the overall satellite cost, maybe we see a 20% decrease in satellite cost. That either translates into greater capital efficiency, or those savings could be reinvested to expand the constellation and offer reduced revisit time or another benefit. Who knows, but there is vast downstream potential for operators such as Planet if Starship does drop costs so significantly, and Planet is already a capital efficient business.

Capital Efficiency

In the same article, Safyan outlines the daily scan of the Earth only requires ~120 Dove satellites. Many current sources put that number closer to 180, but 180 doesn’t match the company’s historical capital investment. In FY 2022 and 2023, when the company was in replenishment mode (i.e., refreshing the PlanetScope constellation, not building new constellations), capex was only $10M.

To square those numbers with reality, I put together the table below showing low vs. high end maintenance capex estimates for the PlanetScope constellation. Long story short, it makes a lot more sense that Planet operates at the lower end of this spectrum than the higher end given the historical level of capex in times of replenishment.

These low end estimates of maintenance capex also align with Ashley Johnson’s comment at the Needham Growth Conference earlier this year that FY 2025 is an anomaly in that they launched two flocks (36 SuperDoves each) to replenish the constellation; normally it only requires one. At ~36 satellites a year for replenishment, that puts us right around the $10M capex number we saw in 2022 and 2023. And, most importantly, at that level of capex, PlanetScope is an extraordinarily capital efficient business even at small scale, an idea that runs counter to the traditional idea of satellite operators.